If you’re environmentally conscious there’s a good chance you use ChatGPT with a guilty conscience.

Even though you don’t know the exact numbers, you instinctively feel that the large language models (LLMs such as Open AI’s ChatGPT and Anthropic’s Claude) must be energy intensive and therefore bad for the environment.

And you’re not wrong, although it’s not (yet!) as bad as you might think.

The number that we constantly see floating around (based on Alex de Vries’s research) is that one ChatGPT query requires 10 times more energy than a simple Google search.

It needs to be said that this comparison is now out of date, as Google has introduced Gemini – an LLM similar to ChatGPT developed by London-based DeepMind – to all of its searches, without the possibility of opting out.

Some estimates are that Google searches therefore now have become up to 30 times more energy consuming.

And indeed, Google, despite having pledged to be net zero by 2030, have actually increased their emissions by around 50% since 2019, mostly due to the introduction of AI. “As we further integrate AI into our products, reducing emissions may be challenging due to the increasing energy demands from the greater intensity of AI compute “, Google wrote in its 2024 sustainability report.

Microsoft had even gone further than Google and promised not just to be net zero by 2030 but also to offset all of its emissions created since the 1970s. Yet it has done the opposite and increased its emissions by 29% since 2020, due to AI.

The Black Box problem

Any numbers you read should not be taken at face value as they are estimates and predictions.

The truth is that nobody actually knows the exact environmental impact of AI, as the tech companies developing AI don’t reveal that information, considering it ‘trade secrets’. It might just be that they don’t do it because it would be bad PR.

What we do know is that they are increasing their operations quickly and massively, as more and more consumers make use of AI.

“Stargate” is a $500billion initiative between Open AI, chip-maker NVIDIA, Oracle, and other stakeholders, that will see the construction of up to 20 new data centres in the coming years in the US alone, each requiring as much electricity as a city of about 100,000 inhabitants. Open AI also plans to open more data centres internationally.

Where we are today

A report by the International Energy Agency (IEA) last year found that currently, data centres use just under 2% of the world’s electricity, projected to rise to 3% by 2030. Data centres are not just for AI but mostly for cloud storage, messenger and social media storage, streaming and anything else that requires data storage. Currently, 20% of data centre energy demand is from AI, a number that is expected to double or even quadruple in the next few years.

Also, it needs to be added that this number is much higher in western developed countries with many data servers. It is 4.4% in the US and even 17% in Ireland.

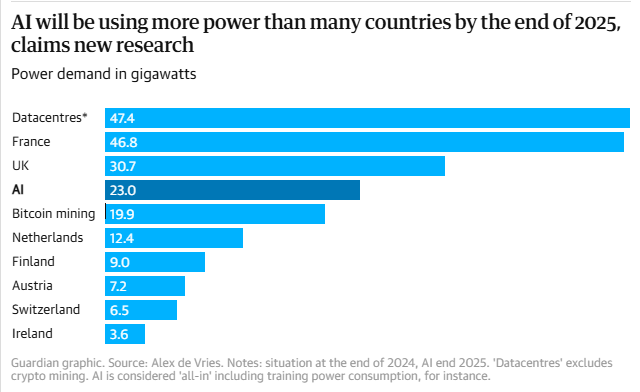

At the moment, the electricity needed for AI worldwide is about that of Switzerland – a rich country with a population of just under 9 million people.

This seems minimal considering that the world population is 8 billion.

But, considering that this is on top of the energy that we are using anyway, it is not to be underestimated.‘Had OpenAI and AI models not been invented, we would save emissions worth that of Switzerland every year’ makes it sound more impressive.

Equally, we have to bear in mind that AI is expanding massively. Here’s an estimate for the end of 2025:

Let’s all chill out a bit

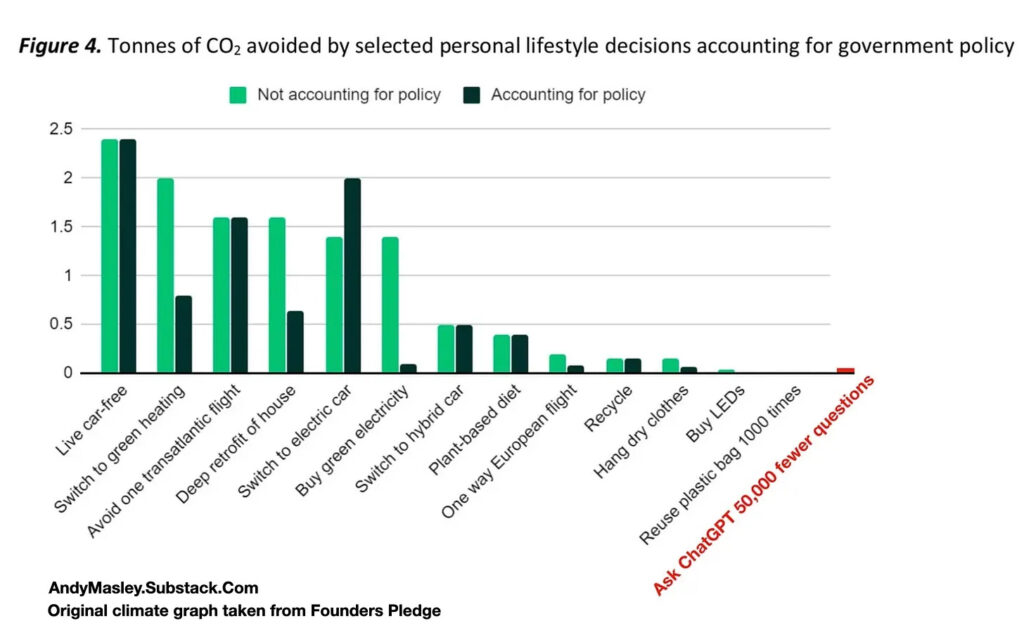

Hannah Ritchie, on her ‘sustainability by numbers’ Substack, makes us aware that we maybe shouldn’t panic too much and that the carbon footprint of using ChatGPT is actually pretty small compared to all the other things we do.

For example, streaming one hour of Netflix uses 26.5 times more electricity than a simple ChatGPT query. Remember, Netflix content is stored on similar energy intensive data centres that are used for AI.

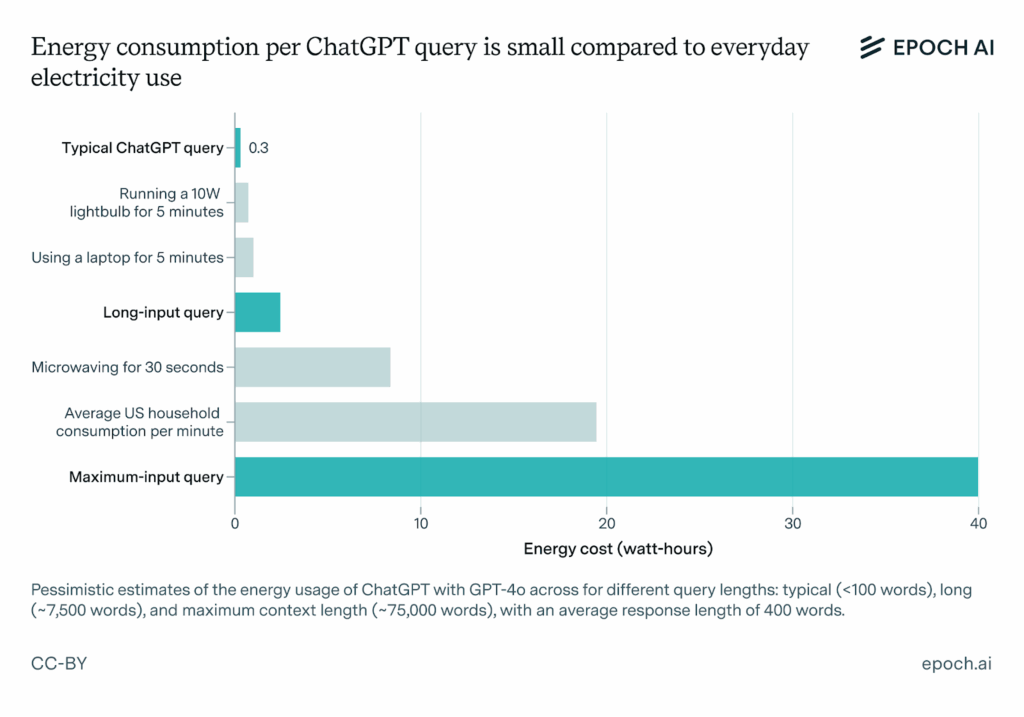

The following two graphs might be helpful:

What this graph shows is that there is an enormous variety of energy needed dependent on the type of query. If you’re creating images of even videos, or asking complex questions it will be much more energy intensive than a very simple query with a short answer.

This graph is interesting because it shows what is most effective in reducing our own carbon footprint.

These numbers seem indeed really small and reassuring, but I need to repeat what I said previously: These are emissions that we produce in addition of what we’re already producing, at a time when we should be reducing our emissions.

Furthermore, the energy consumption of AI will increase drastically over the coming years as models become larger, their user base becomes larger, and there will be more and more models.

The water problem

Another problem is that data centres require large amounts of drinking water to be cooled down (seawater cannot be used as the salt would damage the chips).

They are usually built in dry and hot areas at risk of drought, as low humidity is needed to protect the processing units. The risk of draught is compounded by the fact that data centres are highly centralised, with many built in the same areas.

They are also centralised around cities, where they threaten the drinking water supply of the population.

This has become a particular problem in Spain, where many data centres have been built in recent years in dry and hot areas at risk of drought, with plans to build many more, depriving the local community and agriculture of the little water that is available.

As the effects of global warming will become even more apparent over the coming years, water scarcity will be an increasing worldwide challenge, and the situation in many regions most affected will be made worse by data centres.

Apart from emissions

Emissions generated are a small part of the problems that AI creates.

The Guardian reported yesterday that since the launch of ChatGPT in the UK in 2022, vacancies for graduate and entry-level jobs have dropped by 32%, as companies are cutting staff they think they can replace with AI.

AI makes almost everyone’s job situation more precarious. Jobs become shittier as companies think they can pay employees less and at the same time expect them to produce more with the help of AI.

In many cases reducing humans to ‘babysitters’ of AI, only expected to step in when things go wrong and therefore be paid much less.

What the creators of AI have promised us that it would improve everyone’s life, when in reality it will make their life better as they earn billions, whilst making everyone else’s life harder.

It is nothing but a wealth transfer from 98% of the population to the 2% richest. Due to the utter dependency on technology we can call this a new form of feudalism, with us being the serfs.

Morally dubious

What’s worse is that the only reasons these models are able to exist in the first place are due to large-scale theft of literary, intellectual, artistic and creative property; as well as the exploitation of workers in poor countries.

There are many lawsuits against tech companies by individuals and organisations who accuse them of having used their copyrighted property in the training data without permission. These include authors George RR. Martin and John Grisham, as well as The New York Times, which found entire sections of their newspaper in ChatGPT answers verbatim.

The work of visual artists dries up as consumers think they can generate art using image generators, when these do nothing but reproduce the work of the real visual artists from whom they stole.

Training LLMs relies on an army of low-paid workers to label, clean up and correct mistakes. These are usually in English-speaking poor countries in Africa, exposed to hateful material on a daily basis and paid as little as $2 per day.

Without them, AI models wouldn’t be economically viable.

Conclusion:

It might not be want you want to hear, but unfortunately AI development is not compatible with our values at Friends of the Earth.

We’ve arrived at a bizarre dystopia where your job application is done by AI and then also evaluated by AI at the other end. Nobody wants their job application to be filtered by AI, just as nobody wants to speak to AI when they call a company.

The obvious solution would be too simply not work for companies that use AI in their application process. But this is easier said than done when everyone needs a job and there aren’t enough to go around.

We cannot decouple ourselves from the world we live in.

At the very least, governments should force companies to disclose if they are using AI in their application processes; just as they should force AI companies to disclose their environmental impact.

What we can do is to be aware and reduce our use of AI as much as we can. It is important to remember that overreliance on AI will diminish our capacity for effective research and critical thinking.

Written by Umberto Schramm

Sources:

https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-and-ai

https://digiconomist.net/research

https://www.sustainabilitybynumbers.com/p/ai-energy-demand

https://www.sustainabilitybynumbers.com/p/carbon-footprint-chatgpt

https://www.technologyreview.com/2025/05/20/1116327/ai-energy-usage-climate-footprint-big-tech

https://www.wired.com/story/new-research-energy-electricity-artificial-intelligence-ai

https://www.androidpolice.com/gemini-ai-environmental-impact-costs

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/what-do-googles-ai-answers-cost-the-environment/

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2025/jun/30/uk-entry-level-jobs-chatgpt-launch-adzuna